Reflections on the 100th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

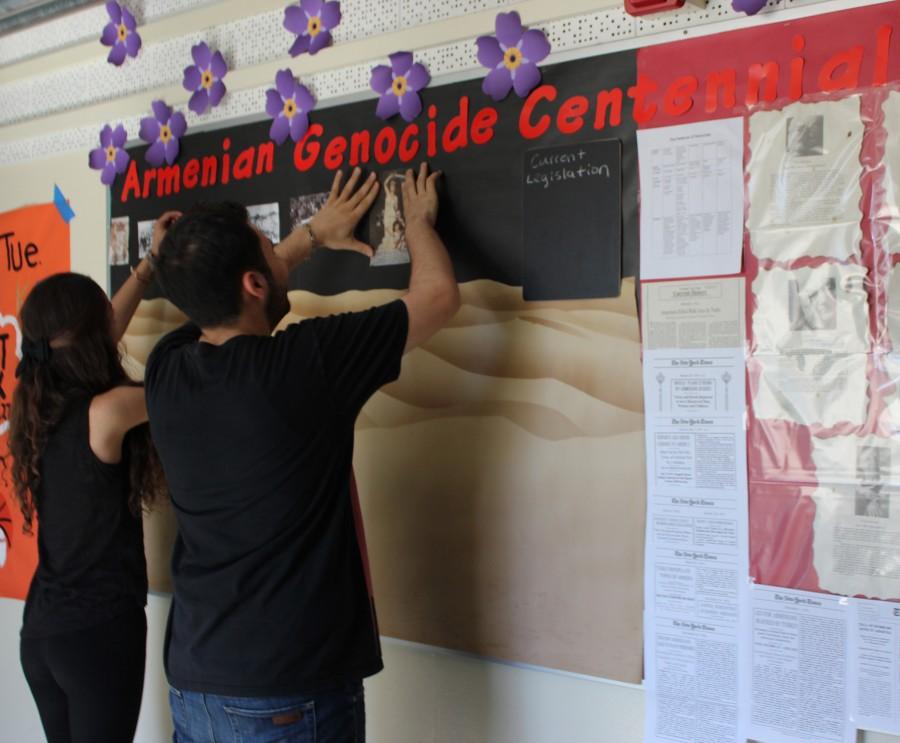

Senior Mher Mkrtchian and junior Jennifer Sahakian assemble a poster about the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide in the school’s main hallway. The poster is meant to inform students about the event.

April 8, 2015

Growing up, my family explained to me the horrendous events of the Armenian genocide by sharing stories about what they had been through. This is a pattern that has occurred in many other Armenian families.

April 24 will mark the 100th anniversary of the brutal murder of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire. The years of the genocide have vanished from Turkey’s history. Nearly 90 percent of Armenia has been seized by Turkey and other countries. The treacherous events cast a shadow on history and cause confusion as to why it has not been formally recognized by many countries.

Genocide is a foreign word to the Turkish government. They have outlawed speaking of the Armenian genocide and denied it for a 100 years. The Turkish Republic has even adopted policies that dismiss any charge of genocide, deportations and massacres that contributed to the extermination of the Armenians.

What I know of the genocide comes from my great-great grandmother Trfanda Guyumjian. Her husband was brutally murdered since the invading Turkish army killed many men after the Armenian scholars were slaughtered. My great-great grandmother and her three sons were taken on the march across the deserts surrounding Syria starting in 1915. Her children died from starvation and exhaustion during the march, along with many others.

She and some others reached Baghdad, Iraq, where Red Cross camps were set up for those who survived. The Red Cross provided clothing, food and medication for survivors. During the year she spent in Iraq, she married a man whose family died on the march as well.

My great grandmother was born during my family’s year-long stay at the camps. They then moved to Beirut, Lebanon, as many Armenians fled to the surrounding countries in desperation for a new home during this time. Around 1946, the route to Armenia opened. They returned to Armenia in 1947.

Those who survived and died inspire today’s Armenians every day to fight for recognition of this horrible cultural destruction.

People walk alongside one another with posters, banners and Armenian flags in their hands and shirts that commemorate the genocide. The most popular shirts say “Our Wounds Are Still Open” in red and white. They were designed by rapper R-Mean who began a movement, “Open Wounds 1915” after his song and music video of “Open Wounds” gained much attention, support and helped to educate people about the genocide. He also writes and sings these songs to continue to tell the stories of 1915 passed down to him by his mother.

Even with these protests, the massacre has failed to gain recognition and this has further frustrated the Armenian community. Though there is a vast amount of evidence that the genocide did indeed happen, from personal accounts to pictures to everything in between, it is still denied by many countries.

“Not recognizing the genocide is almost like people denying slavery or the Holocaust ever happened though there is so much proof that they did. It’s absolutely unacceptable,” junior Sarah Karabadjakian said.

And when history is not acknowledged, it is doomed to be repeated. From 1987 to 1988, Azerbaijan arranged a similar movement to eliminate Armenians from their land as Turkey had previously done. In the cities of Sumgayit and capital Baku, they burned Armenians’ homes, killed thousands in horrendous ways and left those who survived with nothing in desperation for shelter. Those who escaped mostly ran for shelter in Armenia. This event has not been formally recognized at all.

Although 22 countries have recognized the Armenian genocide of 1915, it is not enough. Genocides all around the world have taken place but have not been given enough recognition to prevent future acts. In 1994, yet another genocide occurred due to cultural conflicts; this time in Rwanda.

Crimes as bad as these cannot be ignored or denied, even if these heinous acts are done to what many consider a “minority.” The scar that was left on the Armenian culture will never be fully healed, but formally recognizing the events of 1915— not to mention the crimes of the late 1980s— could give the Armenian community and others who have suffered a sense of closure.

“It’s a humanitarian rights issue. When crimes go unpunished, they will be repeated as we have seen over and over again in history,” R-Mean said. “The Ottoman Empire invented a crime in 1915. The word genocide didn’t exist yet. But since then it has been recurring. What does that tell you?”