During Ramadan, Muslim students reflect on identity and Islamophobia during a pandemic

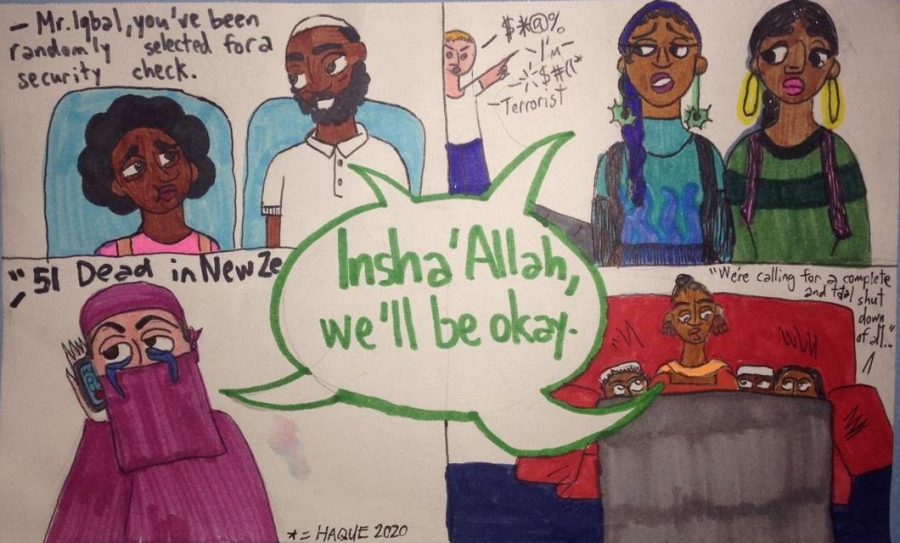

“So it’s especially frustrating to consider that as an American, even during a holy month like Ramadan, my country’s government continues to routinely vilify and discriminate against Muslims both through its domestic and foreign policy,” cartoonist and writer Marjina Haque wrote in this opinion article.

April 24, 2020

When dawn broke and the sun rose on the morning of April 24, around 2 billion Muslims around the world finished up breakfast, prayed and began their fast as part of Ramadan, the ninth month in the Muslim calendar.

During Ramadan, Muslims are encouraged to fast every day from sunrise to sunset for 30 days as part of sawm (fasting in Arabic), the fifth pillar of Islam. Here in Los Angeles, advocacy organization Muslims for Progressive Values (MPV) uses Ramadan as a time to build community and cherish close bonds.

“Ramadan is a very reflective spiritual time for me. I actually find it to be a very disciplined ritual, and I credit Ramadan for being the person that I am, and the discipline I hold,” Ani Zonneveld, MPV president and founder, said in a phone interview. “At Muslims for Progressive Values, it’s a really nice time for us to get together, and breakfast together, and pray together.”

Ramadan during the COVID-19 pandemic is bound to be different, with plans being canceled globally to maintain social distancing. Though many imams and masjids are putting prayers online to help people, the large family gatherings and prayers that Muslims look forward to will have to be celebrated from home and this has devastated many.

“Not being able to follow tradition during Ramadan feels disappointing. This is a time where I feel so connected to Islam and be able to express my faith through fasting and prayer with loved ones,” freshman Zuena Islam said. “I’ll miss joking around with my cousins at the dinner table during iftar. I’ll especially feel downhearted when it’s Eid. Unfortunately, now it’s like a distant dream. I don’t feel as special about this year’s Eid anymore.”

Devoid of fasting, Ramadan is supposed to be a time where Muslims reflect on their spirituality and rekindle a sense of community. For many Muslim families, iftar (the meal one breaks fast with) is the only time they can eat together around a table. We fast to remind ourselves of the things we so readily take for granted.

So it’s especially frustrating to consider that as an American, even during a holy month like Ramadan, my country’s government continues to routinely vilify and discriminate against Muslims both through its domestic and foreign policy. It’s disgusting and deeply shameful to know that in the one country I hold citizenship to, Islamophobia is at the core of its existence.

Islamophobia is defined by writer Khaled Beydoun in his book “American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear” as “the presumption that Islam is inherently violent, alien, and unassimilable”, and we see this belief in exercise every day in the US.

“I wear hijab. I like to show that my religion is important to me. When I’m on the bus, a lot of people will stare at you in a disgusting and vile way,” Islam said. “Sometimes I’ve gotten comments like ‘Go back to your country’ from strangers, and it makes me very uncomfortable.”

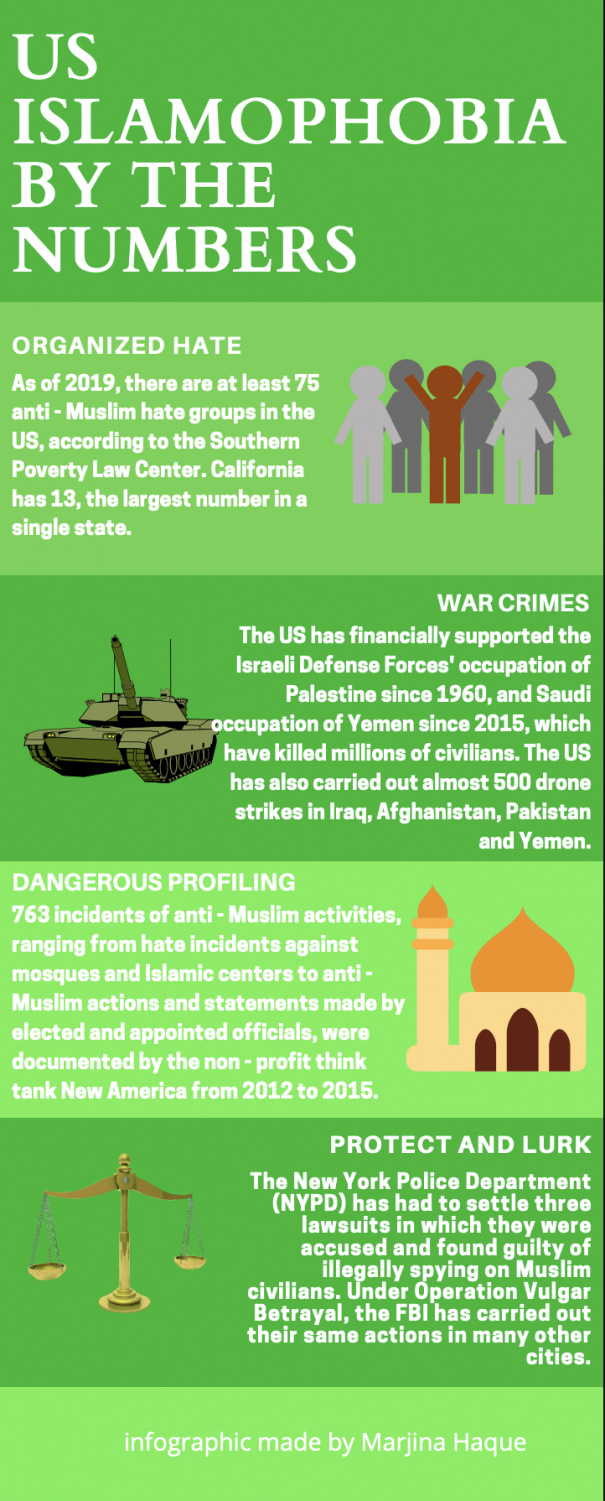

Muslim households and masjids are surveillanced by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and police departments nationwide for fear of housing “suspicious activities”, and people with Muslim names are detained and put through dehumanizing questionings in airports. Comedians like Bill Maher employ dangerous stereotypes about Muslims for a laugh. Muslims, Sikhs and anyone who a xenophobe deems “Muslim” and thus “a threat” runs the risk of falling victim to a hate crime every day they join society.

“Growing up, I would actually lie about my own religion because I was really scared about what people would say about me,” senior Ashiq Siddiqui said. “Islamophobia may have decreased compared to its past, but honestly from personal experience, it’s still happening.”

President Donald Trump is undoubtedly Islamophobic. He has in the past called for a “complete and total shutdown of Muslims entering the US” and has proposed a registry that some fear would put American Muslims in internment camps, not unlike what happened to Japanese Americans during World War II. Even before he was president, he had voiced strongly Islamophobic sentiments in past interviews.

If Islamophobia in the US has escalated and been promoted under Trump, it by no means started with him. Past presidents have also pushed programs and policies that have deliberately targeted Muslims in exercise.

George W. Bush founded the Department of Homeland Security in 2002, which has since regularly terrorized Black and Brown Americans, including Muslims. Bush also invaded Afghanistan and Iraq, resulting in an ongoing war that has cost American taxpayers almost $7 trillion. It has destroyed both countries’ societies, with US soldiers killing and torturing civilians amidst all of it.

Barack Obama continued his tradition when he took office, but “modernized” it by incorporating drone technology into the US Army’s weaponry, which created a massive surge in the death toll of civilians where the US issued drone strikes. Here in the US, Obama created the Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) program, a policing program that greatly contributed to the racial profiling of Black and Brown Americans, especially Muslims.

The US has also historically approached Islam and Muslims as a threat. For example, when the Nation of Islam (NOI) gained popularity in the 1950s and established itself as a part of the Black Power movement of the 1960s, it prompted the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (Cointelpro) to spy on members and tap meetings and lectures.

It’s grim and sobering to realize that Islamophobia, a belief that has detrimental and dangerous effects on me and other Muslims, is as integral to America as the stripes in our flag. How do I pledge allegiance to the same land that tells Muslims we are not deserving of basic humanity?

“Terrorists only use religion as an excuse to justify what they’re doing, and it’s wrong. Muslims don’t even consider them Muslims. Islam is a very peaceful and beautiful religion, but people don’t see that anymore,” junior Ariana Islam said. “Women who wear hijabs, they get discriminated against, and people always ask “Oh, what is that thing on your head?”, and they’re just constantly threatened or seen as threatening; no one can see the beauty in it.”

There are billions of Muslims around the world, and collectively there is an infinite number of experiences and narratives that exist within us. It’s beautiful to me that despite this so many of us are able to come together and practice peace, especially during the holiest month in our calendar.

As I continue to celebrate Ramadan, I’ll continue to do exactly that; practice peace, and hope that Muslims around the world can be reciprocated the same gesture without having to demand it as a basic human right.